For the philosopher Hegel, Art was a means to prepare possible insight about Ideas. Artifacts, it was assumed, were organized with intent to share knowledge, and the development of Art accompanied the development of Philosophy, so said Hegel, from early to middle to end stages. This of course was a progressive framework, driven by the notion that human thought continues to evolve. In this framework, Egyptian art, for example, was judged to be “primitive,” “irrational,” and “amateurish.” Whereas, for example, Italian Renaissance art was judged to be “professional” and “highly sophisticated.” This notion, which prioritizes rationalism and idealized naturalism in art, is easily discredited and, to be fair, Hegel (1770-1831) lived before Romanticism, Realism, Cubsim, Dadaism, and Surrealism.

Donoghue quotes Balthasar on Beauty

Balthasar (1905-1988): “No longer loved or fostered by religion, beauty is lifted from its face as a mask, and its absence exposes features on that face which threaten to become incomprehensible to man. We no longer dare to believe in beauty and we make of it a mere appearance in order the more easily to dispose of it.”

Donoghue (1928-2021), quoting Balthasar: “The elimination of aesthetics from theology and from the whole Christian life has entailed ‘the expulsion of contemplation from the act of faith, the exclusion of seeing from hearing, the removal of the inchoatio visionis from the fides, and the relegation of the Christian to the old age which is passing away.’”

I’m pretty sure I don’t understand the third item in Balthasar’s lament, but to me it seems similar to the idea that one’s Christian faith has been severed from an objective truth that makes the faith reliable.

Edward Hopper and the difficulty of assessment

How to place Hopper’s work in art historical (stylistic) categories and critical orders seems to be difficult. Judgments often have a “but” characteristic to them. Clement Greenberg is among the harshest, writing that Hopper was “simply a bad painter” but “such a great artist.” Several writers point to the deficits of his means but acknowledge the strengths of his compositions.

Is it fair to conclude that Hopper’s oeuvre is: laconic, limited, marginal, provincial, conservative, difficult, and / or plodding? Certainly, he was not: European, avant-garde, purely Modernist, abstract, and / or formal.

Ivo Kranzfelder writes, “(Hopper’s) aim was to find the most concise expression of a given pictorial idea.” (2006, p. 182) Kranzfelder’s summative claim might help explain the subtle irregularities of Hopper’s version of naturalism (especially, his handling of anatomy and linear perspective) and of his use of color (Hopper was a fine colorist, and yet . . .) Hopper was an undeniably original talent, being led by his genius to favor the construction of images of great intimacy, economy, and mystery.

The dilemma for critical opinion, centered on his significance as an American painter in the 20th century, has created a wide and various range of classifications among interpreters and venerators. Even so, his general popularity and his influence on artists have remained intact.

Edward Hopper and linear perspective

I have admired Edward Hopper’s body of work for many years. But the first time I noticed the problems of linear perspective in his work was about five years ago, when I constructed a close copy of Chop Suey (1929.) I was struck by apparent errors of perspective and scale.

More recently, an interpretive copy of Rooms by the Sea (1951) presented similar problems in its construction. The foreground is too large relative to the background, and there is a disruption of linear perspective from one room to another. Hopper was certainly a gifted draftsman and accomplished at the complexities of linear perspective, so what gives? His unusual viewpoints are a drawing challenge to already complicated scenes, and consider how often his viewpoint seems to be from atop a ladder. He was a tall fellow, but not that tall.

So I began to review my collection of Hopper books, and sure enough, many of his pictures seem to have instances of perspective and scale that do not demonstrate a unified system. But neither are they overtly or subtly Cezanne-like or cubist in their handling of illusionistic devices. In fact, his pictures remind me more of the handlings by Bonnard (pre-Hopper) and Diebenkorn (post-Hopper.)

My next hunch was that Hopper was working with memory and observation, expression and naturalism. This hunch was confirmed by reading that Rolf Renner calls out Hopper’s “idiosyncratic use of perspective.” Renner claims that Hopper owes a debt to Edgar Degas, for the “French painter’s concept of the transformation of the real through imagination and memory.” (Renner, 2000, page 86)

Sarton quoted Bogan on Thomas to speculate on "growing up"

(See May Sarton’s Journal of a Solitude entry for September 29, pages 29-31.)

”Yet it is true, and always has been, that innocence of heart and violence of feeling are necessary in any kind of superior achievement; the arts cannot exist without them.” May Sarton is quoting a book review by Louise Bogan of Caitlin Thomas. The extended quotation from Bogan’s book review is immediately preceded by Sarton’s own claim that, “the infant in myself must be forced to grow up, and in so doing die to its infant cries and rages.” And then she follows the quotation with a powerful speculation about her artistic reach, as a poet: “the work of art is a kind of dialogue between me and God . . . (the work of art) must present resolution rather than conflict . . . (which is) worked through by means of writing the poem . . . So there is Hell in my life but I have kept it out of the work . . . And now I am trying to master the Hell in my life, to bring all the darkness into the light. It is time, high time, that I grew up.”

This claim could have radical implications for many Christian makers, yes?

Early career impulse: autobiography versus craft

Being late-career I have plenty opportunity to opine, “(This or that thing) is especially true at this time.” . . . only to recall or be recalled to the facts, to the truth, that this or that thing was true of my own trajectory. Such a recall has been prompted by reading David Daiches’ critical introduction to the work of my favorite author, Willa Cather.

Of her early works, Daiches wrote, “It was a good sign that Cather began her career as a novelist by demonstrating an interest in the craft of her fiction rather than by slopping on to paper her more immediate biographical impulses. . . . Her experiences with a completely objective art, however imperfectly realized, made it all the more likely that she would be able to use her autobiographical impulses successfully when she came to handle them.”

His insight reminds me of my students and my approach to teaching to their development. I am not confident of my own balance of teaching craft versus cultivating autobiographical content, especially in the age of social media. But, 30 years before the advent of social media, I am reminded that as a student and young maker, I thought my own story was pretty special and naturally suitable subject matter.

Philip Guston, Native’s Return, 1957 (cropped.)

Max Kozloff's insight on Philip Guston's painting

Excerpted from May 19, 1962 The Nation.

”Fluctuating between narcissism and self-disgust, unwillingly forced to accept ever newer responsibilities, and pondering his problems past alertness into fatigue, Guston gives the impression of an enormously timid artist.

Yet, how moving is that timidity.”

Guston, timid? But I think there’s truth in Kozloff’s claim. A kind of existential timidity might be part of the peculiar, creative complex that is expressed in his strongest work.

Joyce Carol Oates is an ideal observer of George Bellows

I think what I like most about Oates’ tribute to Bellows is her perceptive attentiveness to individual images, while she speculates about his body of work. George Bellows was an early 20th-century American master; Joyce Carol Oates is much-honored American writer. It’s my opinion that writers rarely get artists right, but more than a few do—John Updike and Julian Barnes come to mind.

Oates’ small volume on Bellows (1995, The Ontario Review) is organized into very short chapters, each one of them about a single Bellows canvas. All of the 16 selected paintings are reproduced, in good color for their small reproduction size.

Oates comes close to being an “ideal observer,” as formulated by Adam Smith. She approaches Bellows with sensitive objectivity, she has a keen awareness of her chosen artifacts, and she certainly has many insights about the affective properties of his work. A Bellows painting is an object of deep pleasure in the fair mind of Oates.

Permission to sail?

“diligent little ships sail

in search of new spices”

This couplet is from Zbigniew Herbert’s poem, “Mr. Cogito on Magic.” (Mr. Cogito, 1974) Herbert is new to this reader, and the Mr. Cogito suite is something of a revelation. Of course, there are no “new spices” to be found, and no little ships to sail, but I really like Herbert’s image—one of a mixed bag—for the fantastic magic of imagination. What if we would permit ourselves to board diligent little ships that sail in search of new lands where unknown spices wait to be discovered? Our voyage might yield a kind of big or little magic, right?

George Bellows, by Joyce Carol Oates

Here’s a great sentence, written by Oates in her essay on Bellows’ The Lone Tenement:

“A tall, isolated tenement building of no architectural distinction looms over them like the shadow of their own unconsidered mortality; the painting’s dynamism lies in its compositional values of contrasting sunshine and shadow, and its sole ‘action’ is the spirited rising of smoke from a distant boat on the river.”

This particular image has become something of a reference point for my own painting.

More Notes on Cezanne

Edward Reep, writing in The Content of Watercolor (1969), made appropriate reference to the significance of Cezanne’s contribution to the medium. (An example from the Cincinnati Art Museum is featured in Reep’s book and shown below.) “If ever there was a need to support the old cliche that ‘watercolor is the medium of the masters,’ we need only point to Cezanne and his genius in composition.”

Reep highlighted these aspects of Cezanne’s genius: tranquility, harmony, sensitivity, rhythmical movements, and dedication. Most of these qualities are recognized by other writers. Reep also picked up on the “concentric focusing” that a few of the most sensitive commentators are aware of (see Dore Ashton and her discussion of rondeur.) I am grateful for Reep’s insight that a Cezanne watercolor can have “a magic blending of invitation and distant recollection;” by this I think he meant that a Cezanne watercolor is both modern and historical.

Another really good sentence

From A Gentleman in Moscow, Amor Towles, 2016:

“The captain had long since returned to his post and the guards, having swapped their belligerence for boredom, now leaned against the wall and let the ashes from their cigarettes fall on the parquet floor while into the grand salon poured the undiminished light of the Moscow summer solstice.”

Whew, and wow! I am early on in this book and am already relishing the exquisite details packed into sentence and episodes of a narrative having tempo giusto.

Dore Ashton's chapter on Cezanne deserves wider audience

Over the years I have read many books and articles on the artist, Paul Cezanne (1839-1906.) I continue to be surprised that one of my favorite Cezanne texts, Dore Ashton’s essay “Cezanne in the Shadow of Frenhofer,” is not widely known. I am not an art historian, but I don’t understand why Ashton’s insightful piece is not found in the bibliographies of other scholarly works on Cezanne. Does it simply “fly under the radar” of that scholarship?

Ashton, who died in in 2017, was an impressive writer, scholar, and teacher, with many publications and awards during a lengthy career. Her most significant work is probably her writing on Abstract Expressionism and the New York school. Ashton published A Fable of Modern Art in 1980; the fable she traces through the histories of 19th and early 20th century French art is Balzac’s The Unknown Masterpiece, from 1831. While Balzac’s fable may also “fly under the radar,” Ashton highlights how well its characters were known among many painters, including Cezanne and Picasso.

I have read her chapter on Cezanne several times, over several decades, and each reading brings more dimension to her insights. Ashton prioritizes Cezanne’s intellectual life and uncovers a foundation for the artist’s uncertainty and anxiety, in a way that most other commentators don’t, because she shows how his keen knowledge of Balzac, Baudelaire, and the poet, Alfred de Vigny was central to his conceptual framework. After one reads Ashton’s careful analysis, the oft-cited aspects of “temperament,” “anxiety,” “attention” or “observation,” “belle formule,” and “certainty” have a richer meaning.

One more thing: in my opinion, Ashton was a splendid writer, demonstrating the “science” and “art” of her subject matter and craft. A Fable of Modern Art is not a quick read, but neither is it a ponderous read. I marvel at the pace of her writing and at its graceful movement. You can find a copy of the book on Amazon or online here.

To embark on a spiritual quest

“To dedicate your life to the intimate knowledge of the most essential nature of any subject is to embark on a spiritual quest.” Jennifer Sinor (quoted from “The spiritual quest of the alchemist,” The American Scholar, Fall 2021)

Yes, okay. And what does it mean “to dedicate your life?” Few people are capable of such dedication to one thing. Intimate knowledge probably refers to knowledge acquired up close, over time; it probably refers to knowledge that is hidden from all but the most patient and devoted inquiries and observations. Because a subject’s “most essential nature” may be dynamic and ambiguous, this is probably the space in any domain where the quest’s deepest struggles occur. The quest becomes spiritual here, because dedication and intimacy alone do not make the quest true?

Links to NetVUE blog posts on topics of vocation

Here’s a September 22 2021 blog post (vocationmatters.org) I wrote as a letter to a younger colleague in the humanities at a teaching institution.

Here’s an August 5 2021 blog post (vocationmatters.org) I wrote on the benefits and limits of using biography to teach vocation.

Here’s a June 15 2021 blog post (vocationmatters.org) I wrote on the subject of using revisiting favorite old texts on vocation.

Here’s a May 27 2021 blog post (vocationmatters.org) I wrote on Natalia Ginzburg’s essay, “My Vocation.”

Here’s a March 4 2021 blog post (vocationmatters.org) I wrote on the subject of using selected poems to teach vocation topics.

Here’s a June 10 2020 blog post (vocationmatters.org) I wrote that reflects on how a pin oak tree planted in the yard is an image of vocation in the fine arts, post-2008 and mid-pandemic.

The example of Ed Young

Most these posts have been about artists of a certain age, artists born around 1930, who have been awarded and have achieved a significant body of work. Ed Young, a Chinese-American born in 1931, is that kind of an illustrator. You will easily find his biography available on many sites; even more impressive to you might be a review of published books—almost 100 titles since his debut in 1962! The two in my collection are Birches (1988, watercolor gouache illustrations of a Robert Frost poem) and Tsunami! (2009, collage illustrations for the adaptation of a Japanese historical episode.)

Let me share in Ed Young’s own words, quoted in editor Anita Silvey’s Children’s Books and Their Creators, two insights that influenced his life of vocation. “(Coming to America to study in college) I took stock of myself and was surprised to find that all the years of drawing and playing were considered a waste of time in a world of measurable assets, of which I had none. . . . (His father’s advice to him when he was in his early 30s) A successful and happy life is one measured by how much you have accomplished for others and not one measured by how much you have done for yourself.” The first quote explains why he initially chose to study architecture, and the second explains why he left a successful career in advertising art to begin creating children’s picture books. I think his pivot from one ethic to the other shows how time and experience have a way of clarifying things about vocation

Where dreams take you

Artist Faith Ringgold (b. 1930) is of the same generation as my parents, and their biographies are certainly different. She was born in Harlem and raised during the Harlem Renaissance. My parents were born in small, midwestern towns and raised in quiet little houses. Despite the difference, I think my mother (now deceased) and Ringgold would’ve gotten along just fine, because their personal narratives would have found authentic intersections.

I highly recommend Ringgold’s book, Tar Beach (1991), to you. It received a Caldecott Honor and won the Coretta Scott King Award for Illustration. Tar Beach first appeared as a story quilt, now in the permanent collection of the Guggenheim. The text and illustrations of the picture book combine to create a fanciful world—a young girl dreams of flying over the cityscape and its landmarks—affectionately grounded in a specific time and its history. Tar Beach will trigger your memory and your child’s imagination. My mother’s “Tar Beach” may have been a rural parsonage yard, surrounded by pastures and fields, a place where she could fly above lonely houses and farmsteads.

“I will always remember when the stars fell down around me and lifted me up above the George Washington Bridge.”

Happy Birthday, Ashley Bryan!

Artist and illustrator Ashley Bryan has accumulated many “firsts” during his long life as an African American creative. A Bronx native, WWII veteran (D-Day), a graduate of both The Cooper Union and Columbia University, a professor at Dartmouth College, a re-teller of folktales and spirituals, an author and studio artist, and winner of many prestigious annual and lifetime achievement awards, Bryan has always advocated for the arts’ power to fight against division and for universal relationships based in aesthetic responses. You can find a good introduction to his biography here.

Reviewing Bryan’s body of work reminded me of the unfortunate biases and assumptions each of us carry for representations and images of Jesus Christ. My church fellowship has favored representations by Warner Sallman and Richard Francis Hook. Most people would agree that neither type is historically accurate, but both types demonstrate the lasting imprint an iconic image can have on the concept we hold on to, in spite of evidence to the contrary. If white people are not comfortable with the image of a black Jesus, their judgment is usually compromised by their willingness to assert their own version of a mostly-white Jesus. Below is Bryan’s image of Mary and Joseph being welcomed to the stable by a boy, from Who Built the Stable? A Nativity Poem, 2012

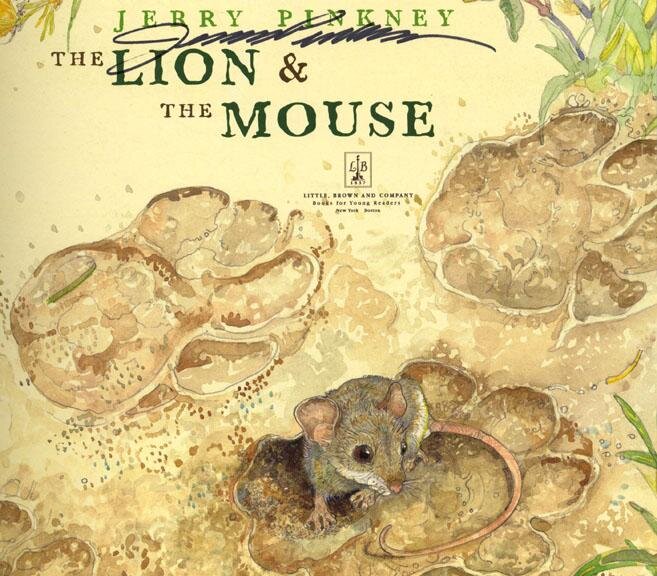

Jerry Pinkney's mentor

One of my closely-held ideas about the vocation of being a visual artist is that, in many cases, a young artist is developed and encouraged by a mentor. Caldecott Medalist Jerry Pinkney (b. 1939) gives credit to Philadelphia cartoonist John Liney (1912-1982) for making an “incredible impression” on him. Liney, an established cartoonist and more than 25 years Pinkney’s elder, invited the young artist to his studio. Just being in Liney’s studio, watching him happily draw and surrounded by his art materials, helped Pinkney understand the possibility of being an artist. Pinkney’s account (from an interview with Leonard Marcus) demonstrates several things about the importance of mentorship of artists: personal invitation and attention; real experiences in a working space; and duration—mentorship happens over time.

Jerry Pinkney’s watercolor illustrations are remarkable for many aspects; I admire his draftsmanship and envy his skills of visual storytelling.

Corduroy, for our times?

In a chapter titled, “I Like You Just the Way You Are,” Ellen Handler Spitz holds out Corduroy, by Don Freeman, as an authentic story of difference and acceptance and friendship. Corduroy is an outsider, an unwanted teddy bear because he is missing a button. Lisa is an African-American little girl, who accepts Corduroy the way he is. Lisa saves her money and goes back to the store to buy Corduroy, after her mother initially refuses to buy him because he is damaged. She takes him home and affectionately sews a button on him—her helpful gift to her bear friend. Ellen Handler Spitz is an internationally respected scholar and author, and her insights for Don Freeman’s story are comprehensive (see Inside Picture Books, 1999.) She notes that Corduroy was published in 1968, the same year as passage of the Civil Rights Act and the year in which Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assasinated.

Don Freeman, Corduroy, 1968